Marine Protected Areas: How can we ensure an effective protection of marine ecosystems?

As the 16th Conference of the Parties (COP16) on Biological Diversity is soon approaching, the Tara Ocean Foundation presents its recommendations to ensure a just and effective protection of 30% of the ocean by 2030, in line with global targets. This article traces back the origins of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs), provides an overview of international targets, and outlines the current challenges facing this area-based conservation approach.

What is a Marine Protected Area?

According to the IUCN, a Marine Protected Area (MPA) is:

” A clearly defined geographical space, recognised, dedicated, and managed, through legal or other effective means, to achieve the long-term conservation of nature with associated ecosystem services and cultural values.”

MPAs can vary in their level of protection, ranging from fully protected areas to areas allowing sustainable human activities, such as traditional fishing practices. Regardless of their level of protection, MPAs’ primary goal must be the conservation of biodiversity.

Numerous studies have provided evidence of MPAs’ multiple benefits, such as:

- Biodiversity conservation

- Ecosystem restoration

- Improvement of fish stocks

- Protection of cultural practices and values

The Origins of Marine Protected Areas

In the early 20th century, a conservationist environmental movement – fueled by influential figures such as John Muir, Gifford Pinchot, and Paul Sarasin – stressed the need to conserve natural areas. In response to the growing need to protect non-human nature and coordinate international conservation efforts, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) was established in 1948 during the Fontainebleau Conference. This location was quite symbolic, as Fontainebleau’s forests were the world’s first protected area in 1861. Since then, many protected areas were created in terrestrial areas.

As the awareness of the ocean’s degradation grew, the need to safeguard marine environments became urgent. The concept of Marine Protected Areas first emerged in 1962 during the IUCN’s World Parks Congress. Since then, the number of MPAs has steadily increased in marine areas under national jurisdiction, while the IUCN published its guidelines and recommendations regarding their establishment. Today, there are 18,888 MPAs established over the world covering 30 million km², approximately 8% of the ocean’s surface.

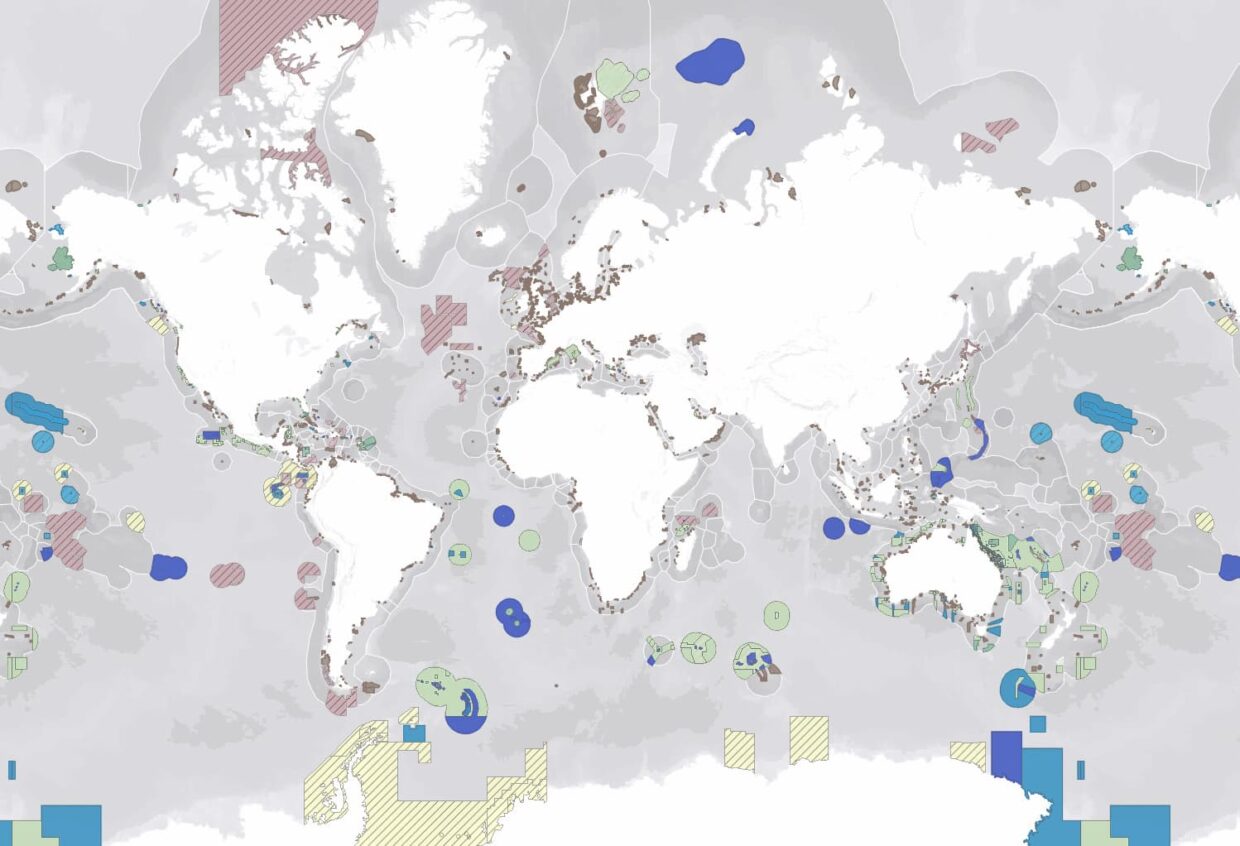

Global distribution of marine protected areas. Strongly protected areas are shown in navy blue, highly protected areas in turquoise, lightly protected areas in dark green, areas with very little protection and/or incompatible with the conservation of biodiversity in light green, and areas with an undetermined level of protection are shown in pink. interactive map Source: Marine Conservation Institute, 2024

Towards protecting 30% of marine areas by 2030

1992 was a landmark year for the protection of the environment and the life it supports, with the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development held in Rio de Janeiro. In addition to the famous Climate Change Conference (UNFCCC), the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) was signed at the end of the Rio Conference, with the aim to protect biodiversity and ecosystems’ heath. Since then, fifteen Conferences of the Parties (COPs) on biological diversity have taken place, each contributing to slow but steady progress towards conservation goals.

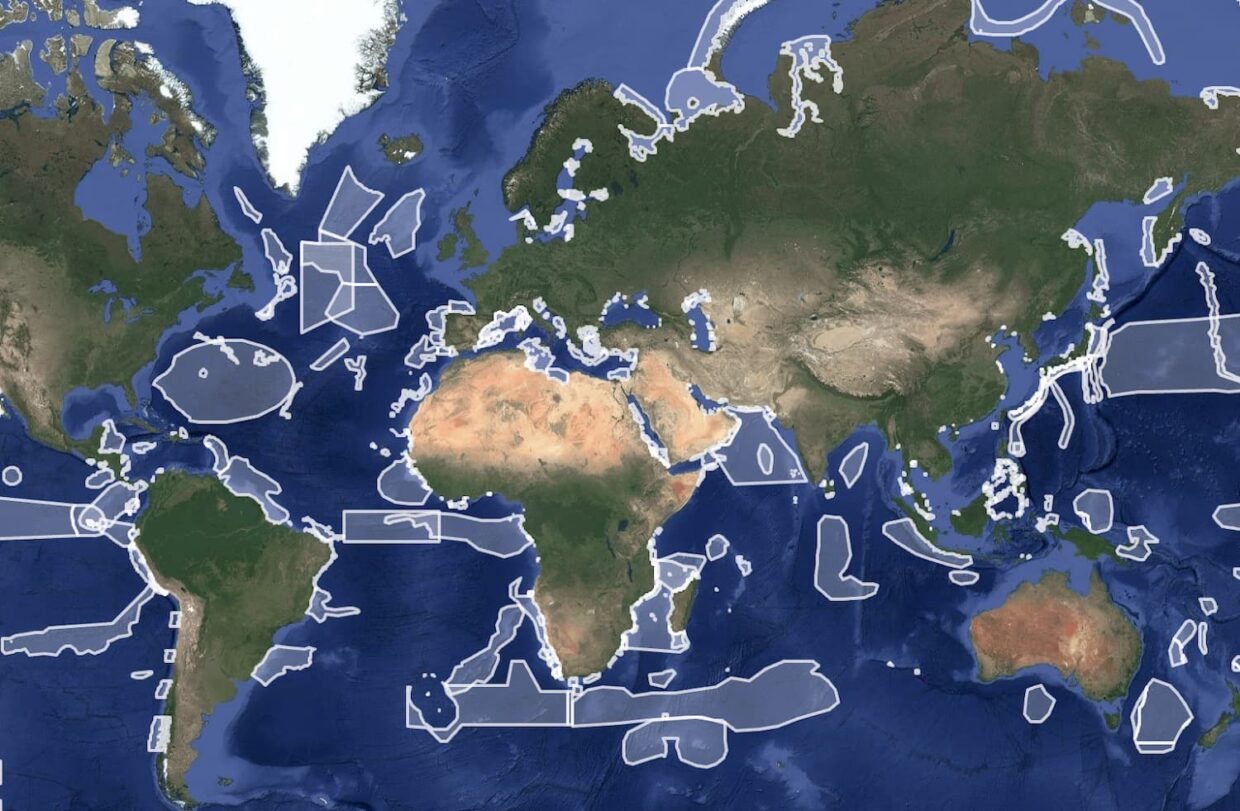

In 2008, at COP9, a list of criteria for the designating Ecologically or Biologically Significant Areas (EBSAs) in the Ocean was adopted, including habitat rarity, presence of threatened species, ecosystem vulnerability, biological productivity, and biological diversity. EBSAs, which do not hold a protection status, are useful tools in targeting areas needing legal protection, through the designation of new MPAs for instance.

Mapping of areas meeting EBSA criteria. interactive map Source: Convention on Biological Diversity, 2024

Two years later, at COP10, member states adopted the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011-2020, whose 11th objective, the Aichi Target, aimed to protect at least 17% of terrestrial and marine areas, as well as 10% of coastal and marine areas, by 2020. The most recent conference, COP15, led to the Kunming-Montreal Agreement, also known as the Global Biodiversity Framework. It is divided into 4 goals for 2050, aimed at protecting biodiversity and ecosystem health, and 23 targets to be achieved by 2030, the third of which aims to protect 30% of terrestrial and marine areas by 2030, often referred to as the 30×30 objective.

The European Union’s 2030 biodiversity targets are in line with international recommendations. Indeed, the 2030 European Biodiversity Strategy aims to protect 30% of marine and terrestrial areas by 2030. The EU’s strategy further indicates that 10% of marine and terrestrial areas must fall under strict protection by 2030.

How effective are MPAs? The risk of “paper parks” and tourist parks

In order for MPAs to guarantee the achievement of international and European biodiversity objectives, their implementation must be effective. To achieve this, it is essential to establish national legal and regulatory frameworks that clearly define MPAs’ status and management methods. In France, for example, there exists no legal text providing a precise definition of an MPA. As a result, the vast majority of France’s categories of MPAs do not meet the criteria established by the IUCN. Indeed, although the IUCN states that no industrial activity should take place in MPAs, industrial fishing is nevertheless authorized in a very large number of French MPAs.

Additionally, for an MPA to be effective, their designation is not enough ; it is also essential to design and implement management plans. A report by Oceana revealed that, despite achieving the Aichi target in Europe, only 47% of the largest Natura 2000 marine protected areas in European countries have a management plan, 80% of which appear to be incomplete. This result highlights the need to strengthen MPAs’ management plans in Europe, by, for instance, setting deadlines and establishing monitoring systems.

Beyond legal issues and quantitative objectives, solely based on surface areas, other factors influencing the effectiveness and quality of MPAs must not be overlooked. There is the need for transparent management practices and objectives geared towards local communities, often forgotten in the process. Marine parks are often created for tourism-related economic goals, which may be granted legitimacy when creating jobs, but, in the long term, these parks can lead to forms of social domination by the wealthy, threatening local traditional cultural and economic practices while creating jobs solely fit to serve tourists’ interests – diving, hotels, and resorts.

Other key elements to the success of MPAs, yet often overlooked, are transparency and sovereignty, which are of particular importance in light of emerging finance-based and market-led approaches to establishing new MPAs. For instance, a recent project to protect the Galapagos Islands in Ecuador will be funded by a hedge fund which lacks transparency and includes Ecuadorian debt securities sold on the financial market as financial products such as “blue bonds”. While new approaches to fund MPAs may be welcome, it is important to remain careful of some financial players’ intentions, as we have already witnessed issues with the carbon market linked to the Convention on Climate Change.

Finally, it will also be important to focus on the protection of ecosystems, beyond the species and habitat conservation approach. In addition to protecting endangered species, we must strengthen MPAs’ capacity to preserve essential functions of marine ecosystems, including CO2 sequestration and climate regulation. This can be achieved by creating networks of marine protected areas that connect different MPA blocks. Focusing on the connection between marine protected areas would be highly beneficial when determining new conservation tools for the high seas. States could, for instance, create protected areas including both areas under national jurisdiction and the high seas. Furthermore, the design and implementation of dynamic Marine Protected Areas, focusing on the seasonal changes of plankton and the marine microbiome, would constitute a holistic approach to marine conservation. This new conservation approach is supported by emerging scientific tools that enable us to discern the seasonal patterns of plankton and other key species.

A seasonal bloom of coccolithophores, a phytoplankton that plays a key role in the biological carbon pump. Source: Plymouth Marine Laboratory

What are Tara Ocean Foundation’s recommendations looking forward ?

The Tara Ocean Foundation actively supports global efforts to protect 30% of the Ocean by 2030, both in France and internationally. We believe that Marine Protected Areas can guarantee the effective protection of marine areas, particularly against overfishing and bottom trawling. We hold the view that the establishment of MPAs must be underpinned by up-to-date and multidisciplinary science, reflecting the complexity of marine life – ranging from viruses and bacteria to large marine mammals. Moreover, we are advocating for participatory and inclusive management of MPAs, alongside transparent funding models that ensure the sovereignty of states and local communities over their resources.