Microplastics: the hidden side of a global pollution

In a special issue of Environmental Science and Pollution Research (ESPR) published on 7 April 2025 devoted to the study of the source, fate and effects of plastic waste in the European land-sea continuum, scientific discoveries lift the veil on invisible microplastic pollution that crosses ecosystem boundaries. This unique compilation of 14 scientific publications highlights the major discoveries made during the Tara Microplastics Mission (2019) to study the origin and flows of plastic pollution in 9 European rivers: the Loire, the Seine, the Rhine, the Elbe, the Thames, the Ebro, the Rhône, the Tiber and the Garonne.

All European rivers are affected

Rivers are the main vector for transporting waste of human origin to the ocean. Every year, they discharge a staggering 8 to 12 million tonnes of plastic debris, which accumulates in all the world’s ecosystems and poses a risk to biodiversity.

In 2019, the Microplastics Mission studied the origin and flows of plastic pollution in Europe’s major rivers. One of the scientists’ expectations was to be able to quantify the density (number of plastic particles per unit volume) and mass (mass per unit volume) of microplastics in the Loire, Seine, Rhine, Elbe, Thames, Ebro, Rhône, Tiber and Garonne rivers.

Over a period of 7 months, a total of 2,700 samples were taken off the estuaries, at the mouths of the rivers, and then in their beds, upstream and downstream of the first major city encountered. Since all the samples were taken using the same sampling methodology, the scientists were able to compare the results from the estuaries of these 9 rivers.

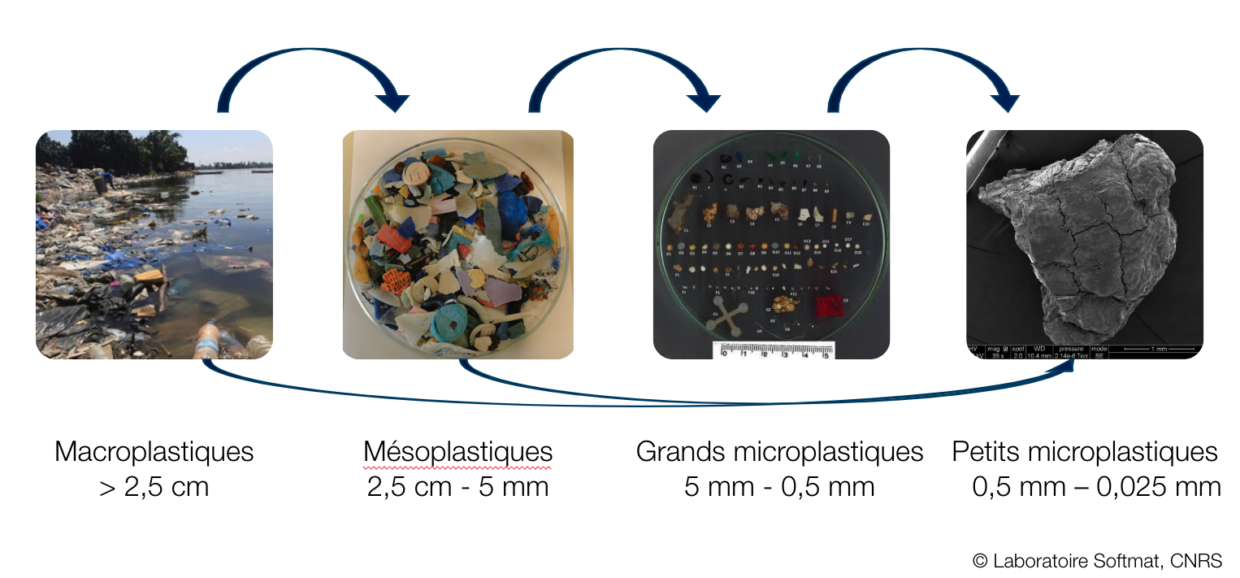

Two sizes of microplastics were studied: large microplastics with a size between 0.5 and 5 mm and small microplastics with a size between 0.025 and 0.5 mm.

The results of these analyses are worrying: all the European rivers studied are polluted by microplastics.

Invisible and universal pollution

Small microplastics: smaller but more numerous

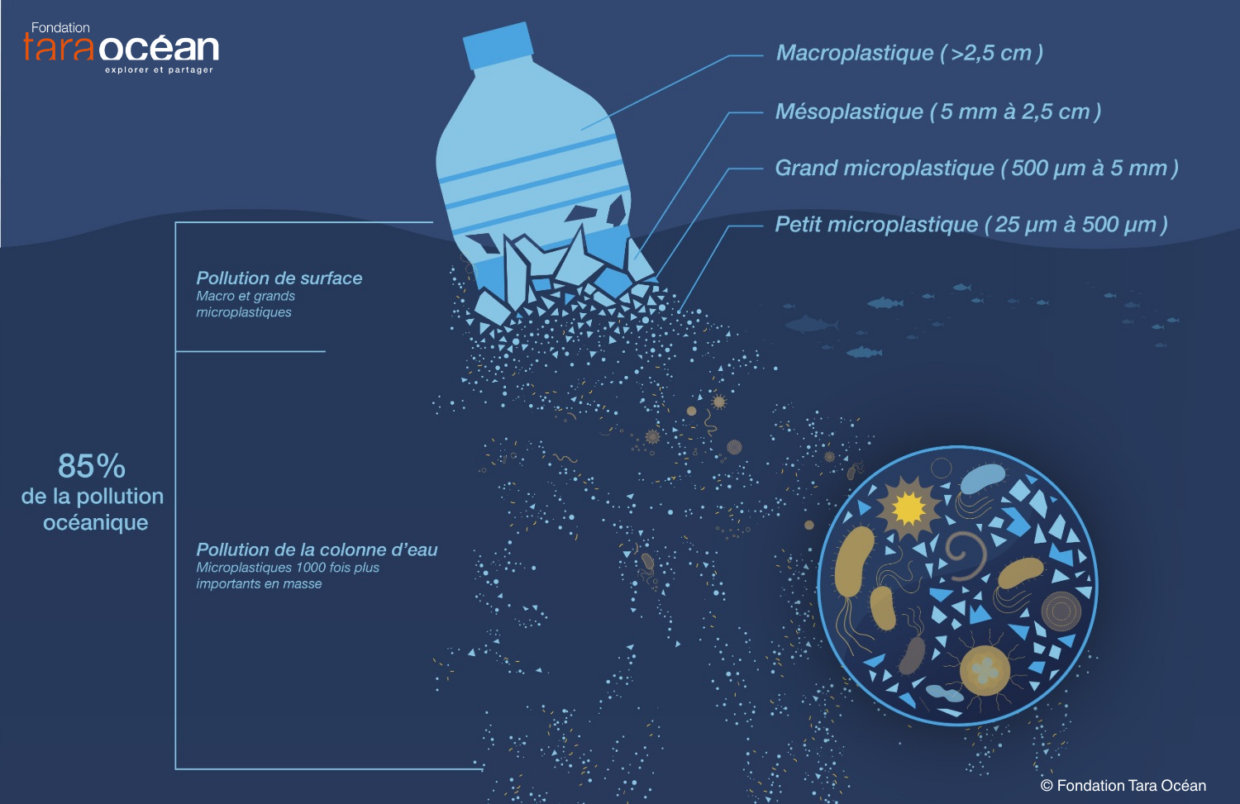

The analyses show that small microplastics (between 0.025 and 0.5 mm) are up to 1,000 times more numerous and heavier than large microplastics on the surface of the 9 European rivers studied.

These small microplastics, invisible to the naked eye, are much less studied, but these results show that they represent the hidden part of the iceberg. Scientists underline their concern about these alarming concentrations in rivers.

These small microplastics are even more likely to be ingested at all levels of the food chain, from microzooplankton to fish.

This discovery was made possible by an increase in technology and precision in analysis methods, in particular by mass spectrometry after pyrolysis of microplastics, a system that pushes back the limits to the infinitely small and is increasingly accurate in establishing mass balances.

From the surface to the abyss, microplastics are everywhere

No ecosystem is spared.

As the Rhône has the highest freshwater input in the north-western Mediterranean basin, scientists have adopted it as a basis for analysis to understand the mechanisms by which microplastics are discharged from a river into the ocean.

Using 3D simulation models to assess the dispersion of microplastics released by the Rhône. The study showed that particles spread throughout the Mediterranean basin in less than a year. More than half of the large floating microplastics are exported to the Algerian basin and further east. Sinking microplastics remain closer to the mouth, in the Gulf of Lion.

The distribution of small microplastics is much more homogeneous in the water column, affecting all ecosystems from the surface to the depths.

Urban and rural pollution, no preference for pollution

The scientists also wanted to find out whether the origin of the pollution could influence its impact on ecosystems.

They did not observe any systematic impact of urban areas on the concentration of microplastics in the water. No major differences were observed between the samples taken upstream and downstream of the largest city closest to the river outlets. This can be explained by diffuse pollution, which comes not only from discharges from upstream towns, but also from agricultural land and the transport of small microplastics in the atmosphere.

A ‘pollutant sponge’ effect and a chemical threat

The impact of microplastics on the aquatic fauna of rivers and the Ocean was assessed by exposing stranded plastic granules to mussels, which are filter feeders that bio-accumulate microplastics as well as the chemical substances they may contain.

The analyses highlight the ‘pollutant sponge’ effect of plastics, which combine with numerous harmful substances such as heavy metals, hydrocarbons and pesticides. They also highlight the toxic impact of chemicals added during the manufacture of plastics, including more than 16,000 additives, 3,000 of which are already recognised as toxic.

The impact of plastics is therefore not limited to the chemical composition of the plastic, but also to the chemical cocktail that the plastic picks up. It is therefore necessary to take into account the systemic dimension of plastic pollution (toxic, chemical and, of course, climatic).

The plastisphere: a habitat for micro-organisms, including pathogens

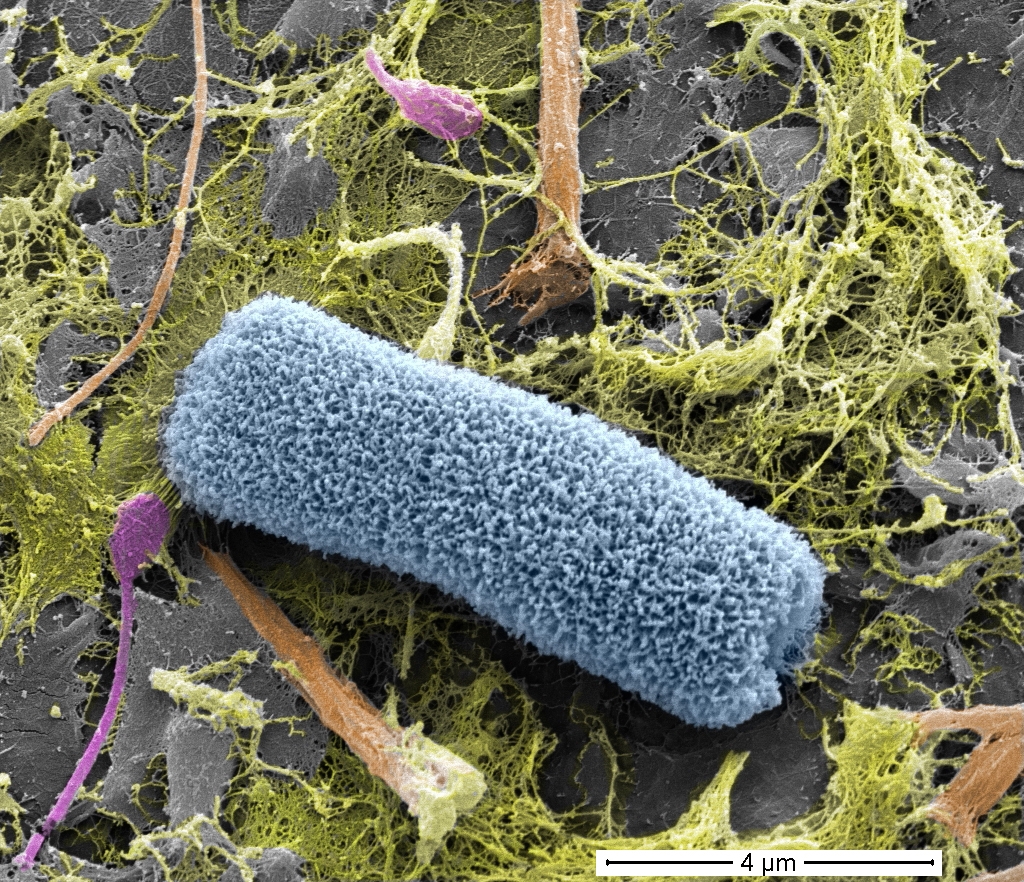

‘Plastisphere’ is a relatively new term used to describe the microorganisms that live on plastic waste in the environment.

In particular, the first pathogenic bacteria virulent to humans (Shewanella putrefaciens) was discovered on a microplastic. This bacterium is responsible for bacteremia, ear infections, soft tissue infections and peritonitis in humans. This study demonstrates the additional danger posed by the dispersal of microplastics in the environment, which can spread pathogenic micro-organisms over long distances. This discovery embodies the link between plastic pollution and global health, establishing a close connection between environmental health and human health.

These plastic “rafts “encourage the transport of micro-organisms from one environment to another, contributing to the spread of the environmental impact of plastic across different ecosystems.

Results complemented by a participatory science initiative

A participatory science initiative with schoolchildren, Plastique à la loupe*, was also introduced in this special issue. For the first time, it compared the distribution of different sizes of waste (macro, meso- and microplastics) on a wide range of French coastal shores and beaches.

Reliable data on the distribution, abundance and types of stranded plastic is needed, particularly on riverbanks, which have received less attention than coastal beaches.

The ‘Plastique à la loupe’ initiative, which currently involves more than 15,000 schoolchildren a year (i.e. 400 classes each year), has revealed major pollution in France by primary plastic granules. This primary plastic forms the basis for the manufacture of plastic products marketed by the plastics industry.

The study showed that these industrial plastic granules, also known as ‘mermaid tears’, make up a quarter of the large microplastics collected on the banks of rivers and along the French coastline.

The study also revealed that riverbanks are mainly polluted by single-use plastics, mostly from food, while shorelines are covered with fragmented debris larger than 2.5 cm.

*Plastique à la loupe’ is a participatory science initiative involving schoolchildren run by the Tara Ocean Foundation in partnership with CEDRE, the Microbial Oceanography Laboratory (CNRS), ADEME and the French Ministry of Education and Youth.

Urgent, systemic action is needed

These studies show the extent of plastic pollution in rivers, confirming the widespread pollution that had already been demonstrated in the oceans. Scientists have shown a direct link between plastic production and environmental pollution. Plastic production has increased by a factor of 2 in the last 15 years (from 200,000 to 400,000 tonnes of plastic produced per year). There is an urgent need to act to drastically reduce plastic production in order to limit pollution at source.

Plastic pollution in the ocean is ubiquitous, with the majority of plastics present being very small, making them difficult to dispose of. This pollution can only increase with the predicted rise in global plastic production, which is expected to triple by 2060.

Plastics are also real vectors of chemical contamination. They act like sponges for pollutants, accumulating and transporting a cocktail of toxic substances. Action is urgently needed to incorporate the chemical dimension of plastics into environmental regulations.

Finally, this pollution represents a direct risk to human and environmental health. The presence of pathogens on polluting plastics establishes a clear link between this pollution and the overall health of our planet, jeopardising the balance of life as a whole. There is an urgent need to take action to limit the health impact of plastic pollution, which affects human health and the equilibrium of Life.