Tara Polar Station: the challenges of science aboard a laboratory drifting in the Arctic

Designed to get stuck in the ice and drift in the Arctic, Tara Polar Station is a scientific station unique in the world that will mobilise around thirty international laboratories per expedition until 2046. Between technical challenges, international collaboration and permanent adaptation, this extraordinary project embodies an unprecedented scientific ambition at the heart of the pack ice.

The challenge of Arctic science

The importance of science and long term observations

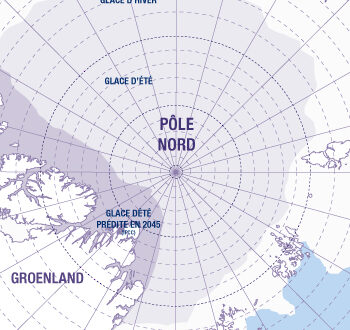

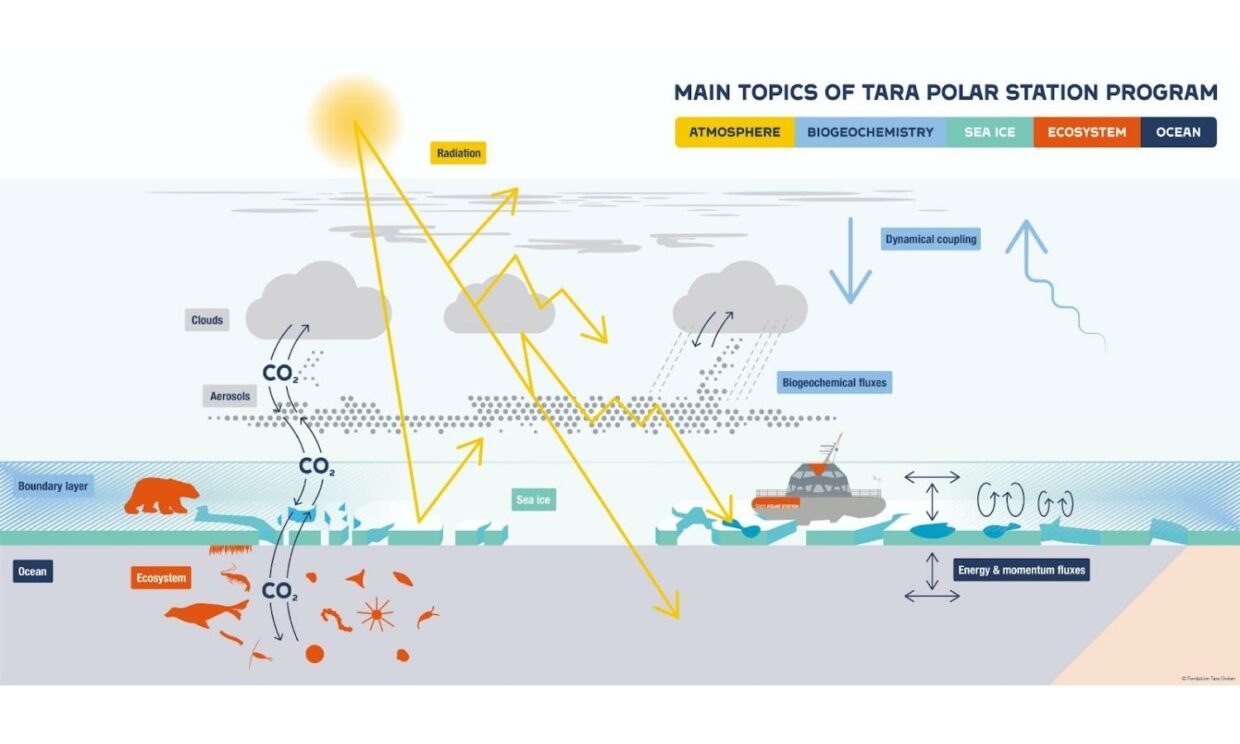

The Arctic plays a crucial role in regulating the world’s climate, and its vulnerability to climate change is placing the pole at the heart of scientific concerns. The rapid changes taking place there, particularly the accelerated melting of the sea ice, are having a major impact on local ecosystems and influencing ocean currents and weather conditions on a global scale. To gain a better understanding of these constantly changing phenomena, it is essential to carry out ongoing, long-term scientific observations. These studies make it possible to document current developments, model future trends and develop effective adaptation strategies.

The Tara Ocean Foundation, aware of these challenges, set about building the Tara Polar Station, a drifting laboratory dedicated to the in-depth study of Arctic ecosystems. Ten consecutive expeditions until 2046 are planned, guaranteeing a rare continuity in the scientific exploration of the Arctic through multidisciplinary research starting with Tara Polaris I in 2026.

These expeditions have 4 major scientific objectives:

- Push back the frontiers of our knowledge of biodiversity by exploring regions that are difficult to access

- Discover the unique adaptations that have evolved to enable life in this extreme environment

- Analyse the consequences of melting sea ice and pollution on these fragile ecosystems

- Identify new molecules/species/processes with the potential for new applications

.

The international consortium: an essential collaboration

Given the complexity of the challenges posed by the study of the Arctic, international collaboration is essential. The Tara Ocean Foundation has therefore brought together a scientific consortium of interdisciplinary researchers from more than 30 institutions1 in 12 different countries for its first Tara Polaris I expedition. This international cooperation facilitates the sharing of data, the harmonisation of methodologies and the development of joint research projects, strengthening our collective capacity to understand and respond to the environmental challenges of the Arctic.

A vision for the next 20 years is being put in place by an executive committee with three co-chairs: Lee Karp Boss, University of Maine, Marcel Babin, CNRS/Université Laval, Chris Bowler, ENS/CNRS. However, each expedition will have a scientific director. For Tara Polaris I, it’s Marcel Babin.

“For more than 20 years, the strength of the Tara Ocean Foundation has been its ability to bring together scientists from a variety of disciplines and laboratories to work towards a common goal: to conduct collaborative research, publish together and share data freely with the entire scientific community.” Clémentine Moulin, Director of Expeditions at the Tara Ocean Foundation.

Building and equipping a research station in an extreme environment

The technical constraints of the laboratory in Tara Polar Station

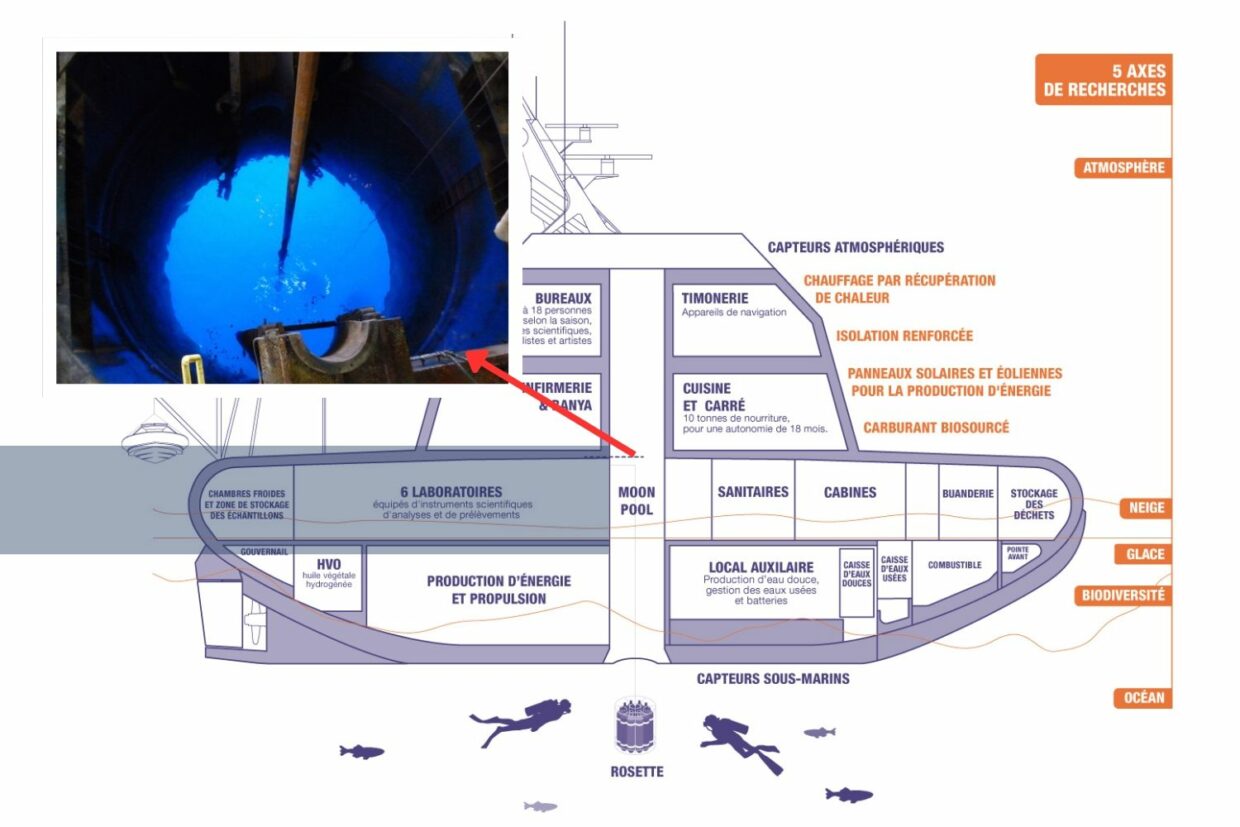

At the heart of the Tara Polar Station, the laboratories have been designed to accommodate a wide range of scientific programmes.

Half of the main deck is dedicated to science, with 5 laboratories: a wet laboratory for handling samples (including ice cores), dry laboratories with instrumentation, and laboratories dedicated to in situ experimentation.

At the centre of the ship, the “moon pool” offers direct access to the sea, allowing ocean water to be sampled all year round.

“Each discipline (biogeochemistry, genomics, chemistry, biology, in water, atmosphere or ice) has its own restrictions in terms of contamination, need for space, chemicals, water, electricity, etc.” emphasises Thomas Linkowski, oceanographer and engineer with the Tara Ocean Foundation.

Even though the station has been designed with relatively spacious laboratories, the challenge is to ensure that all the equipment and protocols work together harmoniously. We have to constantly reconcile scientific rigour and logistical reality in a confined space within an extreme polar environment.

Scientific equipment: resistance to the cold, adaptation to conditions

Not all the scientific instruments on board were originally designed to withstand the temperatures encountered in Arctic winters. While some have already proved their effectiveness in polar conditions during previous expeditions or on ice camps, others will have to undergo their baptism of cold.

In terms of adaptation, as Tara Polar Station is brand new, there will be many tests to optimise the layout of the equipment on board. The aim is to respond to access constraints: some equipment needs to be connected to seawater, others to freshwater, and still others exposed to the open air or sky. Adapting the equipment over time will therefore be a key phase of the mission.

Anticipating extremes, limiting interventions

Preparations will be carried out in Lorient as far as possible, before Tara Polar Station heads for the North. Once the station is in the ice, in September, when temperatures will still be positive, additional adjustments will be made progressively on site.

Instruments will also have to be installed on the ice, but this will take place in the autumn, when the ice begins to form and temperatures are not yet too cold (-15 to -5°C).

The aim is clear: to anticipate as far as possible to limit human intervention when the environment becomes hostile. Apart from maintenance or emergencies, everything is designed to avoid any outside exposure once the cold becomes too intense.

Protocols and challenges of scientific work in the Arctic

Protocols still under development, to be adapted to the polar context

While the broad outlines of the oceanographic protocols are well known, their adaptation to the Arctic context has yet to be refined. At this stage of the project, the scientists involved have not all finalised their specific sampling methods. In theory, the protocols used in the Arctic Ocean are similar to those applied in other marine basins, but adjustments will be necessary, depending in particular on the season, the clarity of the water and the low concentration of plankton.

Thomas Linkowski explains: “In the Arctic, the seasonal contrast is particularly marked: the difference in life in the water column varies greatly between summer and winter, while the transition periods – in spring and autumn – are very rapid. “

These transition periods will therefore probably require specific protocols that are still being defined. The challenge will be to adapt the sampling to the context: the volume of water to be sampled, the duration of filtration and the frequency of analyses will have to be modulated over the seasons.

The challenge of a common scientific protocol for an international team

One of the great challenges of polar scientific expeditions is the harmonisation of protocols. The more methods are shared between teams, the more results can be compared, consolidated and exploited collectively. This has been one of the keys to the success of previous Tara expeditions: well-defined protocols that are simple to implement and therefore “reproducible” on board different types of oceanographic vessel.

Added to this is a major human constraint: in winter, the crew is limited to 12 people, including only 6 scientists responsible for implementing the protocols for the entire consortium.

Anticipating breakdowns to cope with isolation

Working in the Arctic also means accepting a degree of unpredictability, especially when it comes to equipment. While the prevention and management of breakdowns is not very different from a conventional oceanographic mission, the duration of the isolation makes unforeseen events more critical. It is therefore essential to leave with a substantial stock of spare parts, capable of covering several successive breakdowns without the immediate possibility of refuelling.

Preventing breakdowns is above all a question of preparing the equipment properly, but also of regular monitoring (anticipating equipment weaknesses, planning regular maintenance and taking on board the necessary supplies for essential repairs). For unexpected breakdowns, you simply need to have thought about taking on board what you need to repair it. In the event of an unforeseen breakdown, you’ll have to be creative with the resources available on board… or wait.

‘As the saying goes, “to govern is to anticipate”, the same applies to equipment management: “to measure continuously is to anticipate,’ concludes Thomas Linkowski.