A history of polar exploration in the Arctic

Endless nights, intense cold, ice extending as far as the eye can see… the Arctic region is geographically remote and yet we depend on its equilibrium. Located within the Arctic Circle, the Arctic Ocean and the continental and insular region (Arctic lands) form a rich and little-known ecosystem, even though they provide many ecosystem services to all living beings on a daily basis. The Arctic has long been a territory of exploration, but research is becoming essential in this area of the globe increasingly threatened by the impacts of climate change. Let’s revisit the history of polar exploration in this extreme region and how it paved the way for scientific research.

Discovering the Poles

For several centuries, polar exploration has inspired people’s dreams. However, reaching the Poles has always been a challenge for mankind. Adventurers, navigators and scientists all wanted to conquer these territories preserved from all human activities. They embarked towards the unknown to conquer frozen lands, sometimes without preparation for the extreme conditions that awaited them.

Before they could reach this new land, they had to face storms, avoid icebergs and endure long months at sea. These expeditions were long and perilous.

Their motivations were not always mere curiosity and thirst for adventure, they could also be political (conquest of territory) or economic (trade).

Conquering new trade routes

The earliest explorations in the Arctic date back to the Vikings, who reached Greenland around the 10th century and lived there for 500 years. But such early explorations were very rare.

The Arctic was coveted by Europeans as early as the 16th century with the aim of opening up new shipping routes. During the 17th and 18th centuries, several European explorers, such as Henry Hudson (UK), William Barents (Netherlands) and John Ross (UK), undertook expeditions to the Arctic.

Scientific discovery of the Arctic

In the 19th century, explorations were more science-based and led by renowned scientists or navigators such as Sir John Franklin, a Royal Navy officer who attempted to discover the Northwest Passage, and Fridtjof Nansen. In 1893, this Norwegian explorer deliberately locked his ship, the Fram, in sea ice with the purpose of studying its drifting and therefore ocean currents. The peculiarity of this vessel was its rounded hull, which allowed it to be lifted by the ice and thus avoid being crushed. Nansen was the first explorer to get very close to the North Pole (85°56′ N).

The Nansen expedition showed that there is no significant land mass north of the Eurasian continent and that the Arctic Ocean is more than 3,000 m deep. It also revealed that warm Atlantic waters — a branch of the Gulf Stream — penetrate into the central part of the Arctic Ocean as a deep current. These observations made it possible to determine the first principles of ice movement in this area.

A race to the North Pole

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a race began. The explorers Robert Peary (USA), Frederick Cook (USA), Roald Amundsen (Norway) and Richard E. Byrd (USA), all claiming to have reached the North Pole. The feat of Norwegian explorer Amundsen, who flew over the North Pole in 1926, is generally recognized as the most credible.

Who reached the Pole first?

Frederick Cook, an American explorer, claimed to have reached the North Pole in 1908. However, his assertions were disputed. His story was said to be too vague and he made errors in his estimates. Moreover, the two Inuit who accompanied him on this expedition reported that they had never lost sight of the mountains of Greenland.

The American explorer Robert Peary is one of the most famous figures associated with attempting to reach the North Pole. In 1909, Peary claimed to have reached the North Pole with his companion Matthew Henson and a group of Inuit. This claim was also subject to controversy. In fact, Peary had no way to calculate his longitude and probably drifted away from his supposed trajectory. According to a more recent interpretation of his logbook, Peary actually was several tens of kilometers from the Pole.

American explorer Richard E. Byrd led several Arctic expeditions, most notably in 1926, when he claimed to have flowed to the North Pole. This claim was also questioned. His pilot Floyd Bennett reportedly confessed to never flying over the Pole. The time taken to make the round trip was far too short considering the speed of the plane.

Finally, Roald Amundsen is considered to be the first explorer to fly over the North Pole in 1926 aboard an airship, accompanied by the Italian explorer Umberto Nobile. Amundsen was already the first man to reach the South Pole in December 1911, and is famous as one of the greatest polar explorers.

Despite the claim of numerous explorers, there is no absolute consensus on “who was the first to reach the North Pole” because of the many uncertainties surrounding the historical evidence.

An exploration focused on the Arctic’s future

Using technological advances such as submersibles and aircraft, exploration of the North Pole continues to study and map this extreme region.

French polar expeditions

In 1934, Paul-Émile Victor met Jean-Baptiste Charcot at the Académie des sciences where Victor presented a project for an ethnographic expedition project. Charcot supported him financially in his “1934-1935 French expedition on the east coast of Greenland.” Victor brought back 3,500 ethnographic items: sound recordings of traditional songs, a film and thousands of pictures. In 1935, a major report entitled Douze mois sur la banquise (12 Months on the pack Ice) was published in the daily newspaper Paris-Soir. In 1936, Victor succeeded in crossing the Greenland ice sheet from west to east during his “TransGroenland 1936” expedition.

In 1947, the Council of Ministers approved “the founding of French Polar Expeditions in the Arctic and Antarctic lands” and entrusted Victor with their planning. For nearly 30 years, between 1947 and 1976, the ethnologist led French Polar Expeditions, entitled “Missions Paul-Émile Victor”: 17 expeditions to the French territory in Antarctica, Adélie Land, and 14 to Greenland.

One foot on the North Pole

Expeditions had always been conducted in teams until 1978, when the Japanese adventurer Naomi Uemura was the first to reach the North Pole alone, accompanied by dogs and supplied by plane. The first expedition to reach the North Pole without outside help took place in 1986, achieved by Ann Bancroft, an American adventurer, who became the first woman to reach the Pole on foot and by sled. In the same year, Jean-Louis Étienne was the first to reach the North Pole alone on skis, the first Frenchman to achieve this feat.

In the wake of the sailboat Fram: Tara Arctic

Since the 19th century, several drifts have been conducted in the Arctic sea ice:

- 1893-1896 – The Nansen expedition (Norway) aboard the Fram

- 1937-38 – The North Pole-1 expedition (USSR) of Ivan Papanin, a Soviet polar explorer whose airplane landed on drifting pack ice

- 1938-1940 – The Soviet polar expedition aboard the icebreaker Sedov

- 2006-2008 – The Tara Arctic expedition (France) aboard the schooner Tara.

During Papanin’s expedition, explorers measured and determined ice movements and sea currents under the ice pack. They refuted Nansen’s theory that no life existed in the central Arctic Ocean. They also made valuable observations on terrestrial magnetism. The weather observations of this expedition facilitated the planning of the trans-Arctic flights that followed and contributed to our knowledge of the structure of the atmosphere.

The Sedov drift was not deliberately planned. This vessel could not be released from the pack ice by an icebreaker in August 1938 because its rudder had been damaged while locked in ice. With 15 volunteers on board, the ship continued to drift into the most inaccessible part of the Arctic Ocean, where no ship had ever drifted before and no aircraft had flown. The observations of the Sedov’s crew confirmed what had already been recorded during Papanin’s and Nansen’s expeditions: warm waters from the Atlantic Ocean flowing under the pack ice during the whole drift. The Sedov remained locked in ice two and a half times longer than the Fram, although the latter’s drift lasted almost 3 years. The Sedov began drifting much further south than the Fram, and finally descended to more southern latitudes than Nansen’s vessel. The drift of the Sedov lasted only 26 and a half months, indicating that her drift speed was considerably faster than that of the Fram.

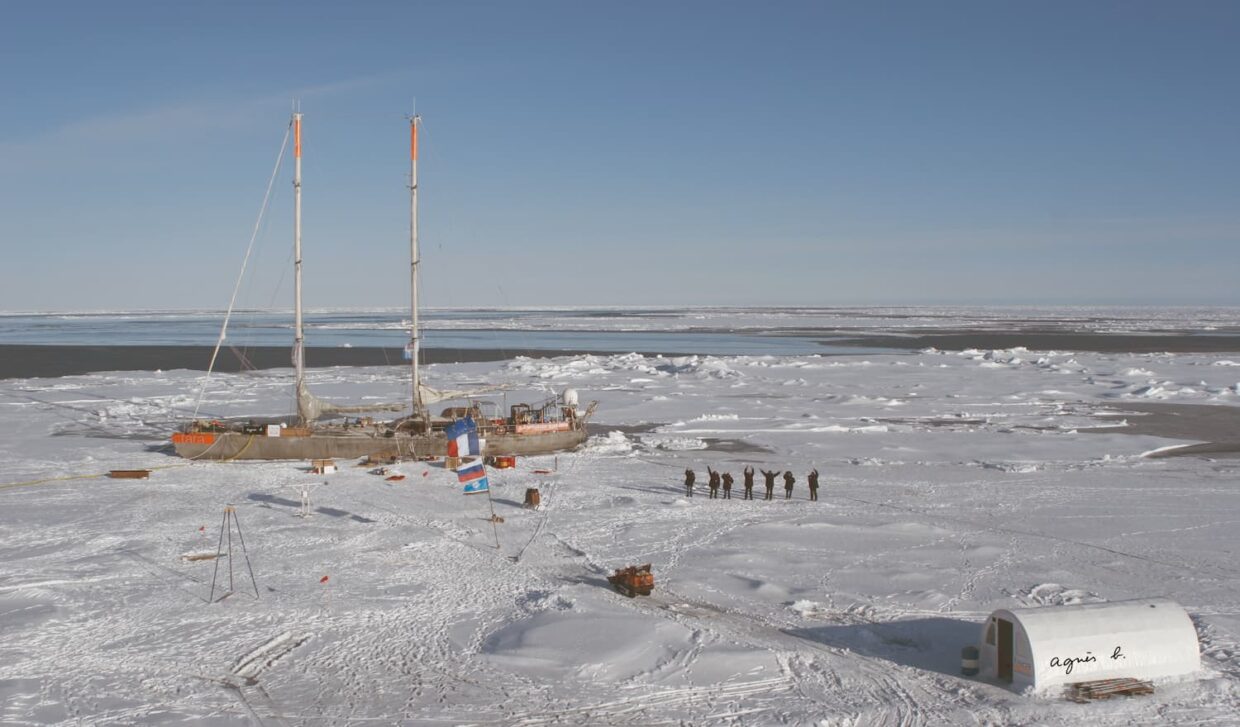

Nearly 70 years later, the schooner Tara was voluntarily locked in ice during the Tara Arctic expedition. She drifted during 507 days from September 2006 to January 2008. The crew on board recorded physico-chemical parameters (air and ocean temperature, pressure, salinity, wind intensity and ice thickness) and also biological indicators to understand the impacts of climate change and ice melt. Since then, this journey to the heart of the climate machine has exemplified the Tara Ocean Foundation adventure, legitimizing the schooner’s role as a fantastic floating laboratory dedicated to understanding and protecting marine biodiversity.

It was an incredible and exceptional experience. The first members of the expedition embarked for 8 months, some even spent more than a year on board. Only one sailor, Grant, stayed the entire 507 days.

Environmental concerns about the future of the Arctic pack ice

The Arctic is a crucial topic of interest due to the exploitation of natural resources such as oil and gas, as well as growing concerns associated with climate change and its impacts on the region and the whole planet.

Climate disruptions are changing this region at a vertiginous rate. These phenomena affect not only the 5 million people living in the Arctic Circle, but also populations throughout the world, and require a comprehensive and urgent response.

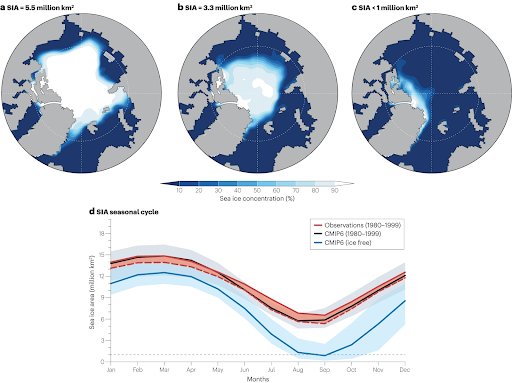

In March 2024, a study published in Nature Reviews Earth & Environment showed that late summers (September) without sea ice are expected to occur as early as 2035 in the Arctic and by 2067 at the latest, if the current warming trajectory remains unchanged. First days without ice in the summer could even take place in the coming years. These projections therefore estimate that summers without sea ice will occur 10 to 15 years earlier than previously reported.

NB: For scientists, an “ice-free” Arctic does not mean a complete absence of ice. The polar region is expected to be ice-free at summer’s end before the end of this decade, and most years by 2050. It is considered “ice-free” when the Arctic Ocean has less than one million square kilometers of sea ice.

a, Pan-Arctic September sea ice concentration with a sea ice area (SIA) of 5.5 million km2, typical for the 1980s. b, The same as in part a, but for 3.3 million km2, typical for 2015–2023. c, The same as in part a, but for sea ice area of <1 million km2, referred to as an ice-free Arctic. d, The climatological sea ice area seasonal cycles for 1980–1999 from satellite-derived observations121 using the bootstrap122 (solid red line) and NASA team123 (dashed red line) algorithms, for 1980–1999 from select CMIP6 models10 (black), and for a predicted ice-free September in select CMIP6 ensemble mean (blue). Red shading indicates uncertainty in the observed sea ice area (bounded by the seasonal cycle from the two algorithms), grey shading the CMIP6 ensemble spread for 1980–1999, and light blue shading the CMIP6 ensemble spread during the decade when the ensemble mean first goes ice free. Although sea ice area is reduced in all months of the year in the future, the loss is predicted to be greatest in September, but winter sea ice returns even after ice-free conditions are reached. Source : https://www.nature.com/articles/s43017-023-00515-9

Faced with the urgency of understanding these changes, which are occurring twice as fast at the North Pole, and the prediction of an ice-free Arctic region in the near future, the Tara Ocean Foundation is continuing its polar commitment by building a second vessel, a combined drifting observatory and scientific laboratory: the Tara Polar Station (TPS).

Once locked in sea ice, the TPS’s purpose will be to strengthen French and international research on the Arctic environment, among the most extreme on our planet, to better understand the impact of climate change on biodiversity and the adaptation capabilities of endemic species.

The Tara Ocean Foundation’s future base, currently under construction, will follow in the wake of the Mosaic expedition’s latest international drift, organized by the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI, Germany) aboard the Polarstern icebreaker.