United Nations Convention on Law Of the Sea, forty years later

On 10 December 1982, in Montego Bay, the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) was signed. Forty years later, what has been achieved?

Starting with the principle of “freedom of the seas”, which has long been enshrined and affirmed in treaties and doctrine, various issues and questions led States, well before 1982, to structure their relations and their hold on these spaces.

However, a timid environmental objective was associated with this movement of appropriation of the seas, illustrated by the implementation of new mechanisms specific to the ocean environment.

Among them, the creation of a dedicated legal regime for fundamental marine scientific research is today what allows Tara to carry out its missions. Forty years and twelve Tara’s expeditions later, environmental considerations have made their way into the law of the sea. We became aware of the specificities of the marine environment and the need to preserve it.

The law of the sea, an evolving history

Not to be confused with maritime law, which regulates private relations at sea, the law of the sea is a law of spaces. It therefore regulates inter-state relations on maritime spaces and organises the exercise of human activities on the sea (fishing, research, wars, etc.).

However, it should be noted that the idea of a “law of the sea” is in fact fairly recent: for a long time, the ocean was seen as a space of freedom, essential to trade and exchange, and therefore not very conducive to the development of legal rules.

However, with the development of marine technologies, maritime navigation developed and States gradually discovered the extent of the Ocean’s wealth. This realisation led to a strong and rapid desire on the part of States to increase their hold on maritime spaces, with the aim of establishing their place in the game of sharing this wealth. This was the beginning of the phenomenon known as “appropriation of the seas”.

From then until 1982, States, individually or collectively, attempted to draw up legal rules specific to the marine environment or to establish distinct zones in which to exercise their jurisdiction. This was done in order to legitimise and control their presence in this space, while maintaining the idea of freedom of navigation.

Thus, the law of the sea did not begin with UNCLOS in 1982. As early as 1930, the League of Nations (League), at the Hague Conference, confirmed the desire of States to create and structure a law of the sea. It was a failure, as the States were unable to agree on the width of the territorial sea. The stakes are high : in this space, the State can exercise relative sovereignty, which is defined as the absolute and perpetual power of a State.

A new attempt was made in 1958 in Geneva, this time under the aegis of the UN, to codify the existing rules. This resulted in four conventions which came into force in the 1960s, dealing with :

➢The Convention on the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone, which came into force in 1964.

➢ The Convention on the High Seas, which entered into force in 1962.

➢ The Convention on Fishing and Living Resources in the High Seas (1966).

➢ The Convention on the Continental Shelf (1964)

However, here too, the States were unable to agree on the width of the territorial sea, and these conventions were soon deemed insufficient to meet the maritime challenges identified at the time.

The limits of these conventions were quickly invoked, beyond the issue of the width of the territorial sea. On the one hand, because the new states that emerged from the waves of decolonisation did not feel bound by what had been agreed in these treaties. On the other hand, the issue of exploitation of the seabed beyond national jurisdictions was raised for the first time. In view of the rapid progress of technologies that are leading to the first explorations, it is a question of guaranteeing that future exploitations take place in the interest of humanity.

Some areas have thus raised more issues than others in their construction, in terms of delimitations and the exercise of state powers within these delimitations. Hereunder is a brief overview of the legal geography of the Ocean.

The territorial sea

This is the 14th century. As states were developing their presence on the seas, they were seeking to establish their control over these areas. However, the idea of appropriation had not yet been put into practice, and the State set up delimitations in a defensive and pragmatic logic, without yet wanting to claim sovereignty.

It was in the 16th century that the notion of territorial sea emerged: this is in fact the space where the State can effectively impose its domination, the width of which is limited to the range of a cannonball fired from the coast (about 3 nautical miles).

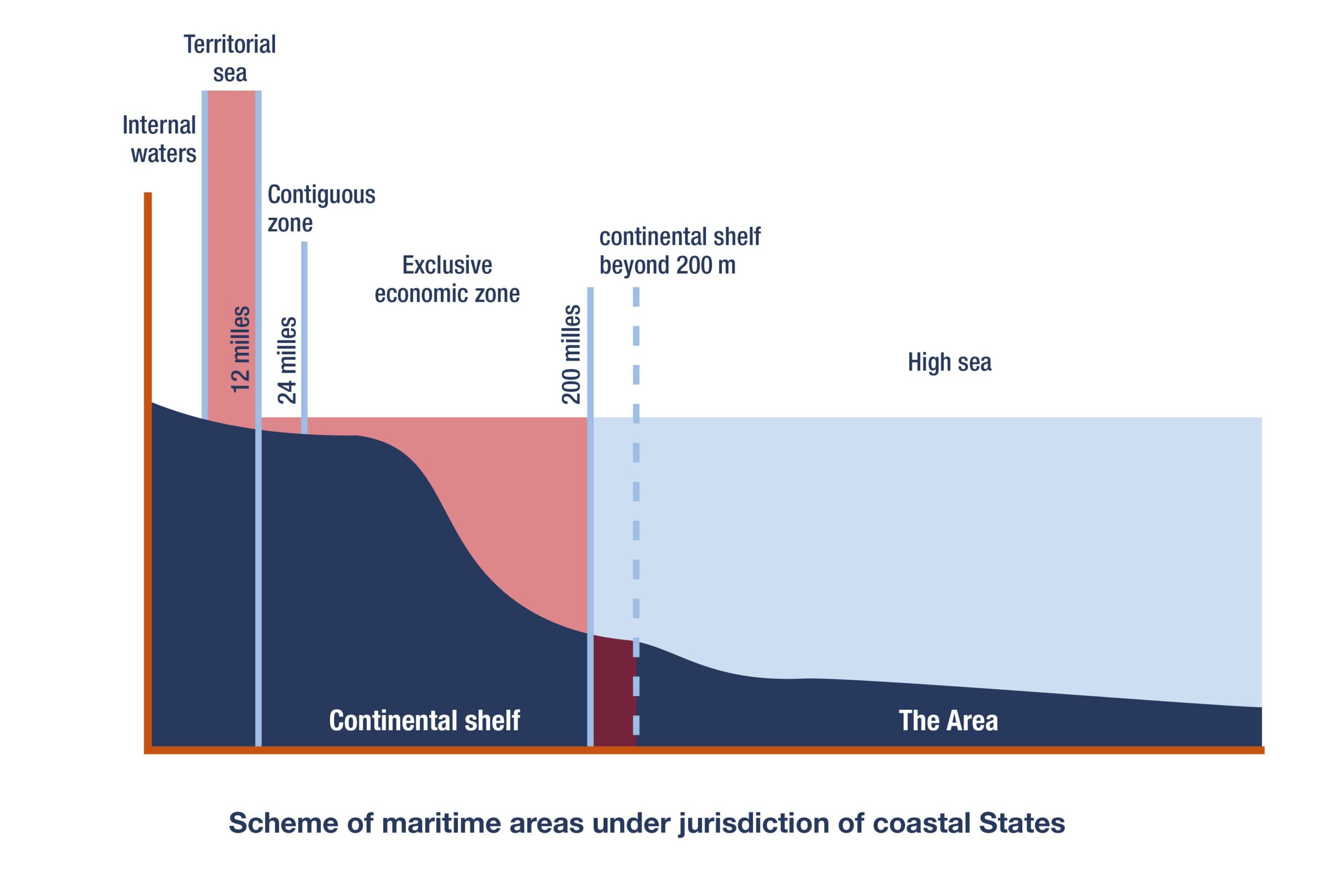

In the 20th century, during the negotiations for the signing of UNCLOS, practice will, not without difficulty, guide custom towards a unification of the understanding of the notion of territorial sea, setting its maximum width at 12 miles. In this space, the State will be able to extend its sovereignty under the conditions defined by the Convention. It must coexist with the “right of innocent passage” granted to any ship, which allows them to cross the territorial sea of a State in a continuous and rapid manner.

The choice of a maximum distance of 12 miles, which may seem small in relation to the ambitions of States, is in fact compensated for by the emergence of the concept of the exclusive economic zone.

The contiguous zone

Extending up to 24 nautical miles from the baselines, directly adjacent to the territorial sea, the contiguous zone is the result of the desire of States to retain policing powers over the sea, to extend their capacity to prevent offences, protect their archaeological heritage or exercise the “right of hot pursuit“.

The Exclusive Economic Zone

We are in the period following the Second World War, a period of economic expansion. States were keen to protect their populations, in other words to ensure their supplies: they therefore increasingly coveted the resources of the sea. This trend began in particular in the countries bordering the Humboldt Current, which runs along the west coast of South America beyond the 12-mile limit and is known for its particularly rich fish stocks.

Gradually, from 1945 onwards, states made unilateral declarations, proclaiming their sovereignty and exclusive jurisdiction over a zone of up to 200 miles, in order to silence covetousness and prevent the exploitation of these riches by others.

But international society did not wish to follow such a sovereignist vision. Therefore, during the UNCLOS negotiations that began in 1973, the law, by compromise, enshrined the possibility of holding “sovereign rights” over this exclusive economic zone. This zone is therefore under ‘jurisdiction‘ and not under ‘sovereignty’. The rights granted are delimited within specific areas and listed in the convention. They have been determined in accordance with the economic considerations that led to the creation of the zone. For example, the State will have sovereign rights in the conservation and management of living, non-living and fishery resources; and in research and preservation of the marine environment. Foreign vessels retain freedom of navigation in this zone.

The continental shelf

Without limiting themselves to the water column, the States seeking territorial expansion in the 20th century also took an interest in the sea bed: its soil and subsoil. At the end of the 19th century, the idea began to be put forward that there was an extension of the continent under the sea, an idea supported by the observation that land mines sometimes extend below the surface of the water… And if the continent extends, so does the territory of the state.

But like the EEZ, international society will limit this right to the granting of sovereign rights to coastal states, limited to the exploration, exploitation and conservation of resources, and which will only have an effect on the soil and subsoil of the sea.

Defining and delimiting this space was therefore not an easy task, as its appropriation was based on economic and political rather than geological criteria. The Montego Bay Convention gives geographical definition criteria, within a limit of 200 nautical miles. However, the shelf may extend beyond this distance, and a state wishing to extend the continental shelf submits a submission to a Commission for the extension of the continental shelf, provided that its claim is accepted by the bordering states. Often, such claims have led to maritime delimitation disputes. One example is the Arctic, where the extension claims of different states overlap and no compromise has yet been reached between them.

International waters: the high seas

A few centuries ago, the high seas corresponded to the ocean in its entirety, a space where freedom of navigation, fishing and trade prevailed. Since 1982, with the appropriation of maritime spaces by States, the high seas correspond to what is not under the jurisdiction of States. It does not include the seabed beyond the continental shelf, which is known as the “Area”, and which is declared to be the common heritage of mankind. It concerns exclusively the water column, and is currently an area of freedom, navigation, research, etc. Although reduced, it still represents 50% of the surface of our planet.

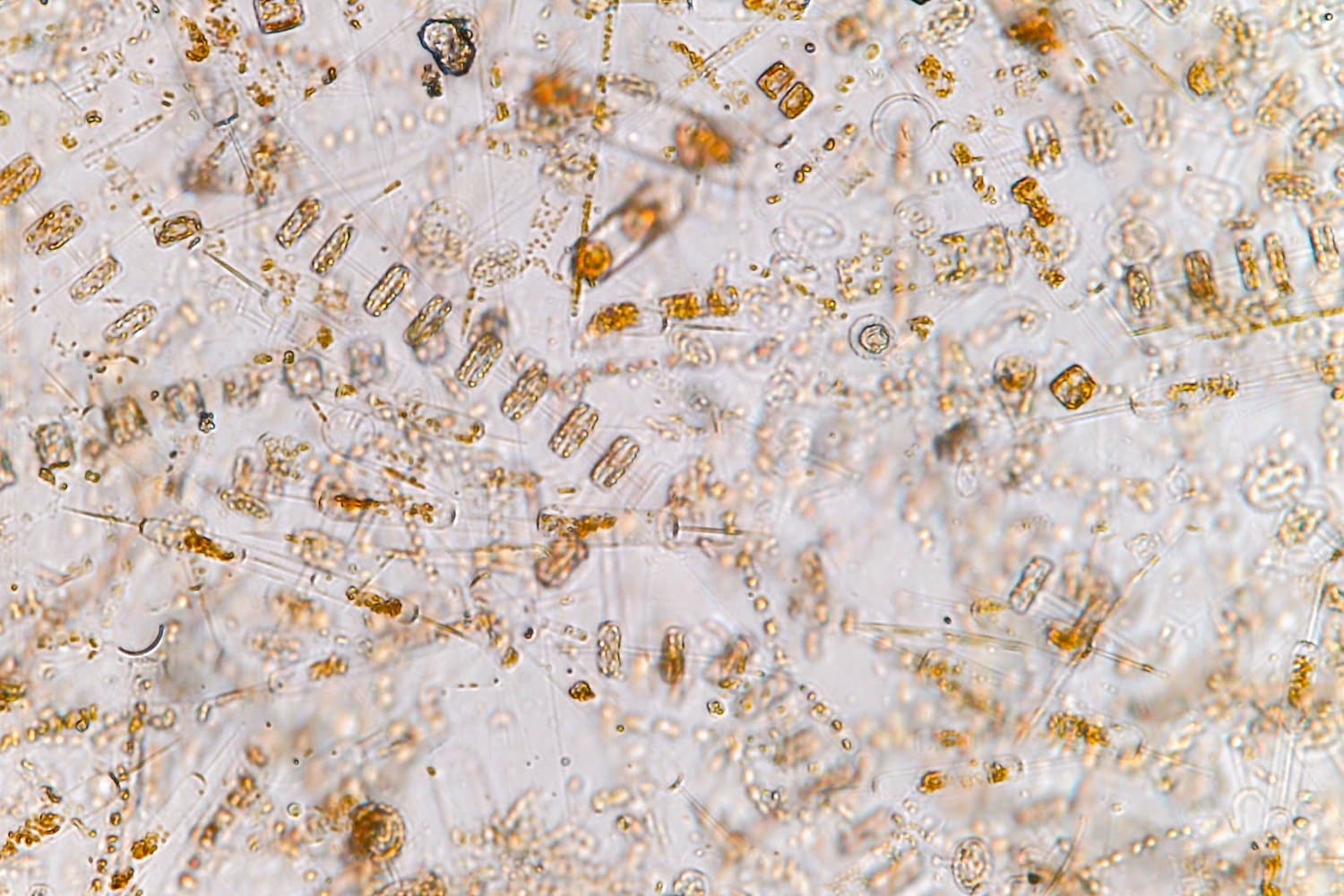

While ten years ago, these international waters were very little explored, scientific projects, in particular the Tara Oceans Expedition, has made it possible to reveal r incredible ecosystems harboring new organisms containing myriads of new genes. These discoveries have fuelled the current awareness of the need to protect the entirety of our Ocean in the face of climate change.

Today, the high seas are becoming the focus of many discussions. It is becoming essential to regulate the activities of States in this area. This is why, under the impetus of the United Nations General Assembly, States have been working since 2004 to draw up an agreement to implement the UNCLOS, designed to protect biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction. It will focus on four major issues:

- Exploitation and sharing of marine genetic resources,

- Area-based management tools,

- Environmental impact assessments,

- Capacity building and transfer of marine technology.

If the negotiations on the Montego Bay Convention lasted nine years, the negotiations on this agreement, known as “Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction” (“BBNJ”), will not be any quicker in the face of an unprecedented challenge: to revise the idea of the freedom of the seas, which is several millennia old, in order to accept the idea of an even greater challenge: that of the necessary preservation of the Ocean.

What protection for the marine environment through the law of the sea?

The development of the law of the sea saw a new theme emerge in the 20th century: the preservation of the marine environment. Thus, it was in 1958 in one of the Geneva Conventions that the issue of the overexploitation of marine biological resources was raised for the first time.

Definitively enshrined and developed in the Convention on the Law of the Sea, the issue of the preservation of resources and the protection of the marine environment was in fact inseparable from that of the management of resources for economic purposes. The exploitation of resources, such as fisheries resources, cannot be sustainable unless their conservation is ensured. Protecting and preserving the marine environment has therefore become an obligation. And if States have the “sovereign right to exploit their natural resources” (Article 193 of the Convention), it can only be exercised in compliance with this obligation.

To this end, States will be able to adopt laws and regulations, in their territorial sea but also in their EEZ, to preserve the marine environment. Often, this will involve implementing the necessary means to prevent, reduce and control pollution caused by human activities. Although the State has a certain amount of autonomy in adopting these measures in the areas under its jurisdiction, there are environmental guidelines, notably from the IMO, with which it must comply. This makes it possible to harmonise the levels of protection developed on the Ocean.

In line with this philosophy, the preservation of the marine environment could not be ensured without knowledge: one cannot effectively protect what one does not know. This is why a legal regime dedicated to fundamental scientific marine research activity was enshrined in the Convention on the Law of the Sea.

Fundamental research is research carried out for the sole educational purpose of improving the knowledge of mankind. It is opposed to bioprospecting, research carried out for the private exploitation of resources, which is not subject to this international obligation of cooperation: it is purely at the discretion of the State to authorise or not this activity in the areas under its jurisdiction.

Because improved knowledge is essential for the effective preservation of the marine environment, the Convention has therefore gone a long way in regulating this research activity. Rather than an article, basic marine scientific research occupies an entire section of the Convention, Part XIII. It is enshrined as a freedom for those who carry it out, always carried out for peaceful purposes, but above all, always subject to the consent of the coastal State in its implementation. This condition, which seems paradoxical, actually ensures respect for the sovereign rights of the State over its natural resources, avoids the plundering of one State’s resources by another, and prevents the commission of environmental abuses in the name of research. The State retains discretion in assessing these circumstances, and the obligation to cooperate is not intended to apply to its detriment. In particular, this has provided developing countries with the means to protect their resources and interests.

An obligation to cooperate in the service of Tara’s marine scientific research

The Montego Bay Convention implemented the obligation for States to cooperate in order to facilitate the exercise of basic marine scientific research. This obligation now allows the schooner Tara to travel the world with the aim of obtaining and sharing knowledge associated with the marine environment.

This obligation to cooperate is in fact at the heart of our activity. The request for consent from a coastal State to carry out research in the waters under its jurisdiction is made through diplomatic channels, six months before the expedition. But obtaining the so-called research permit is not the end of the matter, quite the contrary. So, throughout the schooner’s passage through its waters, we have to keep the state informed of the progress of our activities. And, as the expedition comes to an end, we share the results of our research with the state authorities. In this way, cooperation is ensured in both directions, reciprocally between the research State and the coastal State.

Finally, the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea is for Tara the reference when it comes to implementing an oceanographic expedition, without which its research activity would not be as free and consensual. And, after 12 expeditions and in preparation of a 13th, after 20 years of history of the Foundation and more than 300 scientific publications, it is clear that the Law of the Sea is an essential instrument to respond to the present and future challenges around the protection of the Ocean.

By Juliette Schramm, Legal aspects (sea law) officer at the Tara Ocean Foundation