How are the logistics of an oceanographic expedition organized?

Let's unveil the backstage logistics of oceanographic expeditions. Scientific campaigns are subjected to fantasies and make young and old dream about their oniric and adventurous nature on the other side of the world in a constrained and extreme environment. The other side of the story is much more pragmatic and concrete. The on land teams contribute to a colossal logistics, less attractive and notorious, yet not less important to the achievement of the expeditions. Anticipation, organization, methodology, prioritization, coordination, communication, adaptation and improvisation are the key words of the hidden jobs of expedition logistics. The plan is never unique and is declined in the plural form, the best is arranged and the worst is foreseen.

The origins of modern oceanographic campaigns: from the Challenger to the schooner Tara

In 1872, the HMS Challenger set sail for a four-year scientific mission that is considered retrospectively to be the first modern oceanographic campaign. The Royal Navy ship traveled approximately 65 000 nautical miles across the Atlantic, Southern, Indian and Pacific Oceans. The Challenger was modified and adapted for the occasion and was fully equipped: laboratory, microscope, sounding cables, trawl net for sampling and dredging, aquarium, alcohol, temperature and salinity measuring instruments etc. The Challenger expedition brought back millions of samples and made numerous observations on the marine environment. A whole coordination that had to be anticipated and that could be qualified today as “expedition logistics”. The schooner Tara has inherited from these first oceanographic campaigns and continues to actively study the Ocean ecosystem.

How does the Tara Ocean Foundation prepare a maritime expedition?

Anticipation beforehand

Each expedition has its own identity and addresses a scientific hypothesis or question.

– Scientific coordination

Prior to the expedition, the Foundation’s logistics team works closely with the scientific partners on the definition of the mission, its scientific issues and its geographical scope in order to translate the research objectives into operational terms: What and how to sample? Why and where?

In addition, a host country may express logistical and legal prerequisites for obtaining the permit:

- an outreach stopover to meet with the locals,

- the boarding of an observer (a naval officer, a researcher, a government representative),

- the data, analysis and sampling results’s sharing,

In short, there is no guarantee that these permits will be issued, which requires the Foundation and its teams to be very flexible and adaptable.

– Port logistics and administrative procedures

In addition to the anticipation related to scientific coordination and legal issues, the schooner Tara, like any ship, must be able to stop in the host countries for administrative procedures, crew rotations and supplies (food stocks, fuel, liquid nitrogen, etc.). This set of threads at the heart of the logistical knot must also be untangled before the expedition leaves.

-> Which port will be able to accommodate the schooner?

->Which quay will be the most appropriate and accessible and will allow a good visibility for Tara?

->What will be the focal point in the host country?

->What are the formalities for entering and leaving the country?

->What are the regulations in terms of immigration, customs and health protocols?

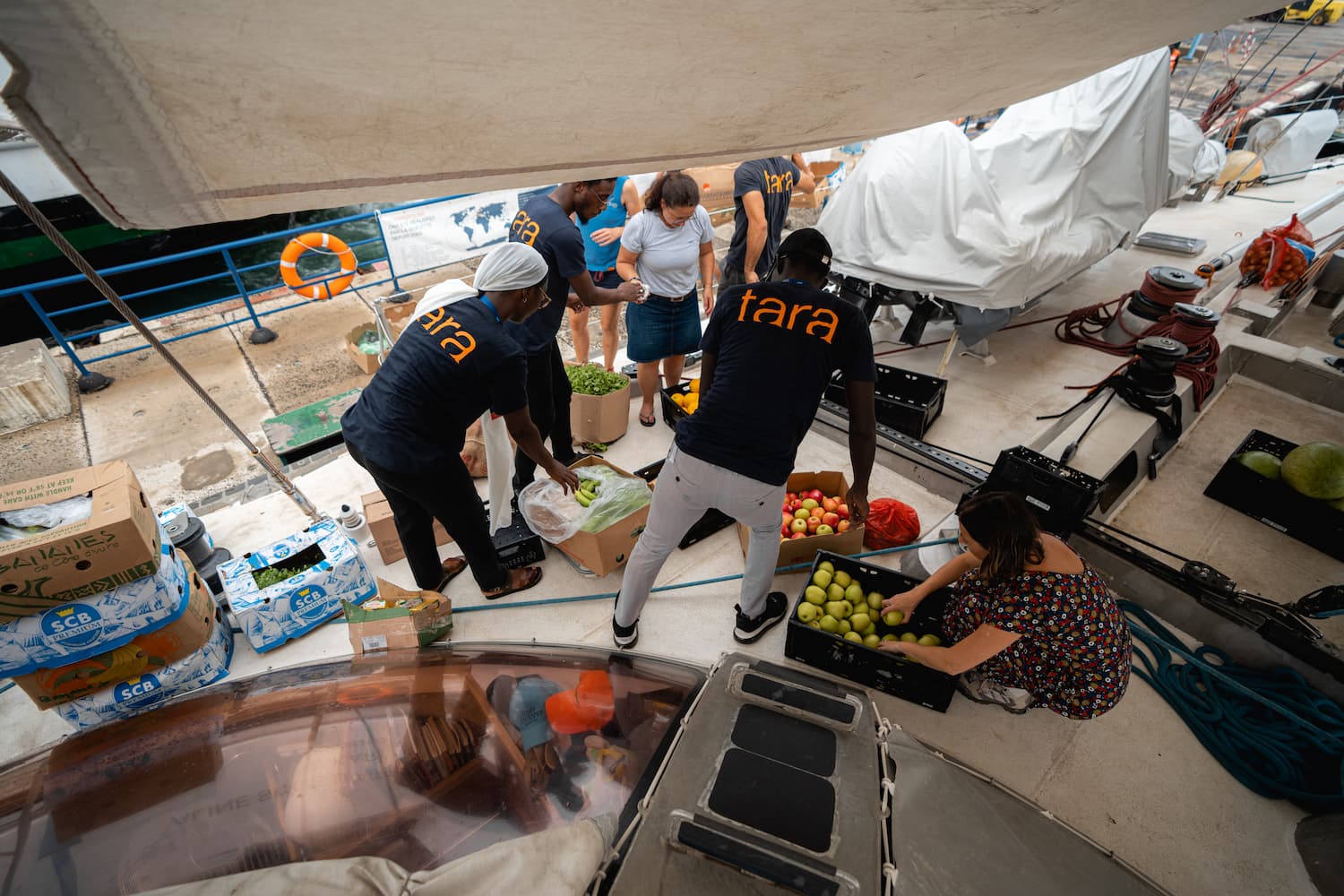

->How do you organize refueling and resupply?

The arrival of Tara requires contact with various maritime and port’s local agents in order to have an overall view of the constraints on site but also of the possible negotiating leverages. The idea is to have established a good network locally and to be able to react in all circumstances from France if a problem should arise.

It has happened that our contacts in the countries were not convinced that the schooner’s arrival in their country was real, and therefore did not mobilize, until the bow of the boat was sighted in the port. And then everything accelerates

– Administration of research permit’s applications

Once the scientific subject is characterized and delimited, the Foundation first applies for the necessary research permits delivered by the host countries in order to obtain the required authorizations for scientific sampling in foreign Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ), as defined by the 1982 Montego Bay Convention. This procedure requires 6 to 8 months’ advance notice before the vessel enters the country and must go through the French Ministry of Europe and Foreign Affairs and the French embassies in the countries. Numerous exchanges with the local authorities on the research project may be needed and it may happen that, at the last moment, the permit request is rejected, the Tara schooner is forbidden to enter the country’s EEZ, the itinerary is modified and the expedition is altered.

Real time improvisation

Once the expedition has started and the schooner Tara has left its home port of Lorient, the marathon begins for the on land logistics team. It is a question of following the campaign and the navigation schedule in real time, orchestrating the team rotations and stopovers, meeting the technical needs of the marine and scientific crew, organizing supplies and the shipment of instruments and consumables.

The main challenge of logistics is communication, to ensure that everyone is informed, that issues and problems are presented in order to save time and efficiency and that everyone moves forward at the same pace. It is imperative to act as a bridge between all the people involved in the campaign and to be the connecting point between the schooner, the teams on board and on land and the scientists, and to create synergies between these groups in order to stimulate the emergence of ideas. The multidisciplinary environment in which the logistics team operates requires them to adapt to the different terminologies and jargons used by the crew and scientists, among others. Not to mention the various languages and cultures that have to be taken into account in the organization of the expedition.

In logistics, time is fundamental, whether projected on the long term or rooted in the short-termism and immediacy of crisis management. The schooner Tara, through its scientific expeditions, sails in the waters of very different countries and in a variety of political contexts. Even if many aspects are prepared in the long term, a last-minute hazard can always occur: administrative setbacks, logistical surprises and diplomatic misadventures. There are many examples of this, and it forces the Foundation’s teams to be on call and available almost all the time.

– Human logistics

Thus, the Microbiomes mission was conducted during the global COVID-19 pandemic. During the first months of the mission in Chile, the crew was not allowed to disembark or go ashore during port calls, confining themselves on board behind closed doors for months. The schooner was dependent on the health authorities and had to work with shipping agencies, incurring huge costs not foreseen in the initial budget. Hard bargaining was required to obtain a favorable outcome.

At the time, given the resurgence of COVID-19 in the country and the world, the Chilean state decided in a few days to close its borders. An imperative crew rotation had to take place to replace the teams exhausted after months at sea and by confinement. In twenty-four hours, tickets had to be changed, PCR tests had to be carried out, authorisations required to travel had to be adapted, members of the expedition stressed by their embarkation had to be reassured, etc.

– Technical logistics

As the expedition progresses, nautical and scientific equipment inevitably gets damaged and sometimes needs to be replaced to avoid jeopardizing the expedition. For example, a new pylon had to be sent to Argentina for the CTD-rosette (part of an instrument that takes water samples with Niskin bottles and measures conductivity, temperature and depth).

In practice, it is necessary to hire an international freight forwarder who will take charge of this equipment from its storage place to the foreign country where Tara will be in stopover and take care of the related customs issues. In reality, at that time in Argentina, there had recently been new presidential elections, resulting in a change of government. The administrations were in transition and therefore demobilized, the cases were temporarily interrupted and, consequently, the instrument was held by the customs authorities for an indefinite period of time. All possible levers had to be considered in order to clear the instrument in time out of the customs and thus avoid the campaign being delayed from its initial schedule.

– Logistics at the heart of political tensions

Once the research permits are granted, the schooner is allowed, under certain conditions, to come and sample in the EEZ of the host country. The theory may seem simple, but the practice is not systematically so and reserves its share of unexpected events.

Tara‘s expeditions have already been trapped between the different authorities of the same country, crystallising numerous internal political tensions, or have already found themselves at the heart of inter-state disagreements and diplomatic conflicts, two countries claiming the same EEZ for example. It should be remembered that Tara is a French-flagged vessel, so when the schooner sails in foreign waters, the ship represents France. In order not to be instrumentalized and not to legitimize the position of one country over another, it has already happened several times that the navigation schedule and the scientific programme were modified at the last moment. In such cases, the logistics team has to make the decision in collaboration with the direction, the ship, the scientists and the French Foreign Affairs ministry, evaluating the risks, the challenges and the adaptation solutions.

Logistics after the expedition

The expedition does not end when Tara returns to its home port’s wharf. After months at sea, it is then time to put the schooner in dry dock (i.e. to take the ship out of the water) for several months of work during which the schooner will be dismantled, inspected in its entirety from the rudders to the engines, and completely refurbished by the crew. This maintenance also concerns all the scientific instrumentation which must be adapted for the next expedition in order to meet the demands of the researchers involved. The remaining stocks must be inventoried, instruments must be sent for recalibration so that they keep their accuracy, and the scientific equipment needed for the new protocols must be installed.

Furthermore, the host countries that allow the schooner to sample are far from uninterested in what has been undertaken in their waters. In the weeks following the departure from the country’s waters, it is therefore necessary to communicate concretely on what has been done, what the ship has collected, and on the first observations made: this is what is known as a “preliminary report“. Then, at the end of the campaign, new reports, known as “final reports“, are requested by the countries, in order to provide them with the raw data from the expedition and information on the expected analyses and results. This is not as simple as it sounds, as science takes time and reports are requested under time pressure. It is up to the logistics teams to act as an interface between the scientists and the countries, to try to reconcile these two timetables. The stakes are high: if the reports are not sent in due time, the countries may well take sanctions, such as banning Tara from returning to their waters in the future.