The high sea: how to protect the little-known biodiversity of international waters?

From February 20 to March 3, 2023, the next - and hopefully last - negotiation session of the Treaty on Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdictions (BBNJ) will take place in New York. The Tara Ocean Foundation has been working alongside science for more than 10 years to compensate for the lack of protection of ecosystems in the high sea, and to better understand their essential role in the great natural balances.

What is the High Sea?

The concepts of freedom and infinity have often been associated with the human conception of maritime space throughout history. In the early definition of the Dutch jurist Hugo Grotius (17th century), the Ocean was declared a free and limitless space (mare liberum), which escaped all State sovereignty (res nullius).

But beyond this general conception, there is a very emotional link that connects us to the Ocean. It terrifies, just as it hypnotizes. We all have our own image of the Ocean built by our personal history but also a common culture fed by an imagination full of strong emotions, from stories, legends and myths that are told in books, movies or even in songs!

The construction of the law of the sea, which governs relations between States in maritime spaces and regulates activities at sea (not to be confused with maritime law, which regulates private relations at sea), gradually created legal frameworks setting the responsibility of States in coastal zones; whose first international definitions were applied during the 1960s. Several conventions thus institutionalized the roles of States, notably through the concept of territorial sea, in which the latter can exercise their sovereignty.

A few years later, the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) was signed in 1982 in Montego Bay, which constituted the founding act for the law of the sea. With this agreement, the high sea gained its contemporary definition: it is the area beyond 200 nautical miles (approximately 370 kilometers) from the coast, corresponding to the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of States. This almost boundless space, therefore recognized as the high sea, corresponds to almost 71% of the surface of the Ocean, nothing less than 50% of that of the planet!

The legal regimes of the law of the sea are still being constructed today. Some States have indeed the possibility to claim rights of exploration, exploitation and conservation of maritime soils and subsoils beyond their EEZ, if the country’s continental plate is extended by the nature of the maritime subsoils. The most striking example is the Arctic zone, where countries’ requests for extension overlap, without a compromise having been reached yet.

A common good essential to life on Earth

With the entry into force of UNCLOS in 1994 (between the signing of an international convention, here in 1982, and its application, a period of adaptation is required), the high sea became part of international law, thus finding a definition in an effective legal regime. However, if Montego Bay does define rules of exploitation and navigation for the maritime space, as well as rules for the exploration of the sea floor, it does not protect its biodiversity. Hence, the norms only regulate human activities, and not the protection of living organisms.

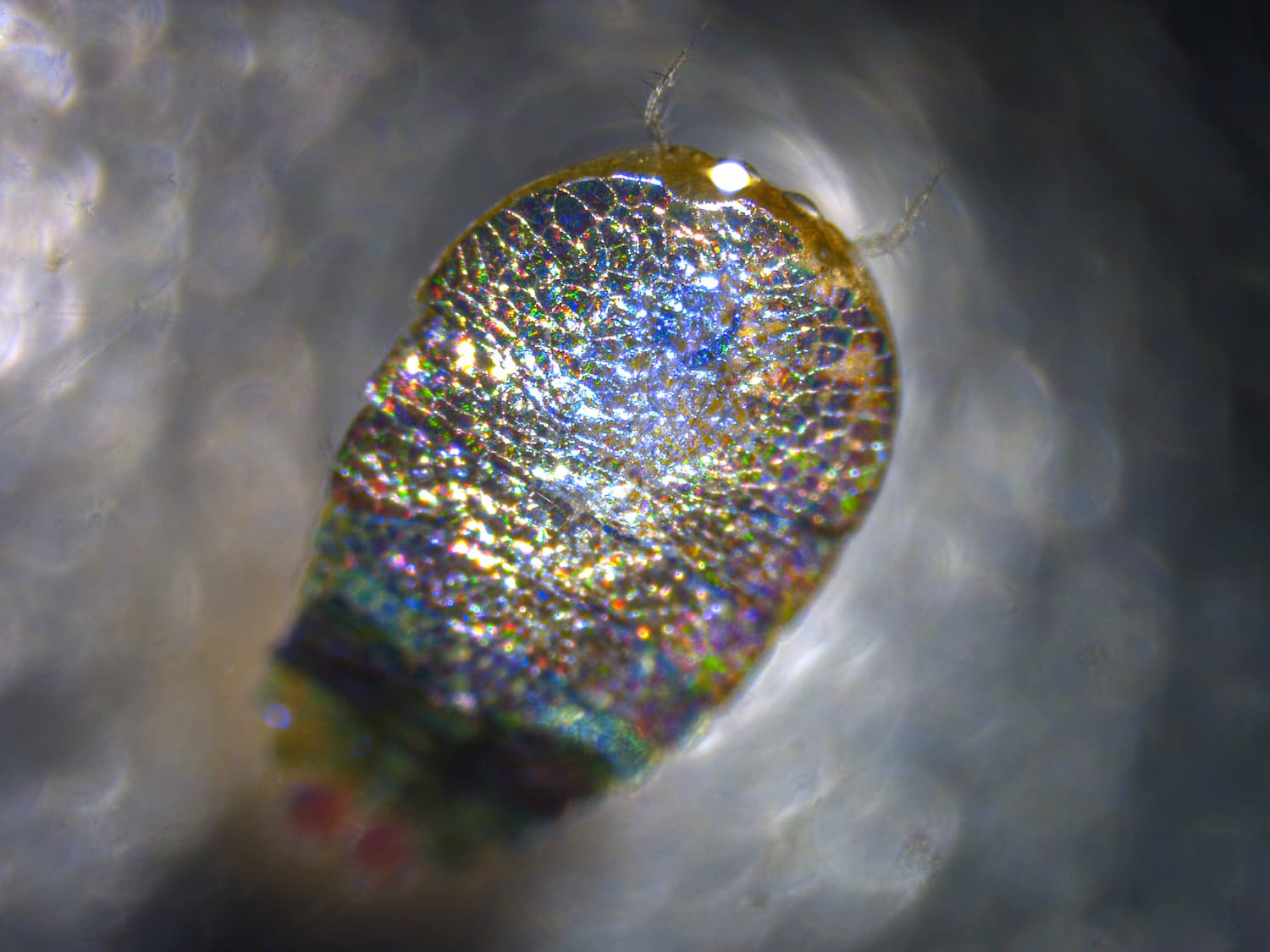

When the Convention was written in 1973, experts and decision-makers were not yet aware that the open ocean – although seemingly infinite and empty – in fact hosts a rich and essential planktonic biodiversity, almost invisible. It was only in the last decades of the 20th century that we discovered that these planktonic ecosystems represent more than 70% of marine life. They are at the origin of many vital processes, such as carbon sequestration and oxygen production, which are essential for all forms of life on our blue planet.

Thanks to scientific research, we are also realizing that these tiny organisms – bacteria, viruses, protists, algae, small crustaceans – are fragile and already suffering from the impacts of climate change, overfishing, and various pollutions. The evidence provided by science of the magnitude of the consequences of anthropogenic activities (pollution, climate change, etc.) on the whole planet, including the high sea, is indisputable: practices such as intensive fishing, seabed exploration or maritime transport must therefore be controlled and limited, even in the open sea. It is essential to update and contradict Grotius’ conception, to reconsider our relationship with this space that was thought capable of absorbing our wastes indefinitely and handling our unrestrained development model, to realize the unsustainability of our system.

The construction of the treaty on biodiversity beyond national jurisdictions

[2003 – 2013] First steps towards a binding international treaty

In a context of rising awareness on the magnitude of the ecological crisis, a first dialogue aiming at proposing a complementary text to the Montego Bay Convention took place around 2003, with the objective to include measures for the conservation of marine life in the high sea. In 2006, an informal process was initiated at the United Nations to propose an international treaty on marine biodiversity beyond national jurisdictions (BBNJ), beginning its long journey within the United Nations institutions.

In the corridors of international organizations, a few countries took the lead and initiated consultations, proposing frameworks and themes, or trying to develop avenues for the thorny issue of financial compensation for the exploitation of marine resources. In 2011, the European Union and some States such as Brazil, South Africa and Costa Rica agreed on a first draft, structured in four axes, or “packages”:

- Management of marine genetic resources and their use ;

- Area-based protection tools, including Marine Protected Areas (MPAs);

- Environmental impact assessments for high seas activities;

- Capacity building and technology transfer.

The structure and title of the text have then been established, and have not changed since: “Intergovernmental Conference on an international legally binding instrument under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea on the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction”.

This first text was presented in 2011, during the preparatory sessions for the Rio+20 Conference on sustainable development, which was held a year later in Brazil. At the Rio Conference in 2012, the text was endorsed, and the negotiation process at the United Nation was set to begin in 2013.

[2013-2023] 10 years of negotiations: overcoming national interests to approve an ambitious treaty in 2023

The States have been negotiating this complex text at the United Nations since 2013, still based on the architecture built in 2011. In this long process common to all multilateral conventions, milestones have been reached: informal negotiations until 2015 to agree on the objectives and framework of the future treaty; preparatory conferences from 2015 to 2017, where some reluctant countries were able to gain time; and finally adoption of the resolution of December 24, 2017, which initiate an Intergovernmental Conference to draft and approve the text of the future treaty.

The decision-making process within the United Nations, on this seemingly essential subject, is long and difficult to implement. The underlying issues of this treaty are indeed complex and challenge traditional political arrangements. Iceland, Spain and Japan, fishing countries, for example, have joined forces to remove fishing from the treaty. Emerging countries, especially the least developed, wish to set mandatory funding for research. The industrialized countries have the ambition to protect their companies and their patents on genetic resources. Russia, China and the major countries of the South want to protect their sovereignty over strategic areas and refuse to support the creation of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs). Moreover, as the BBNJ treaty is supposed to be binding, the bodies responsible for regional seas aim at minimizing the scope of the text in order to protect their mandates over these specific areas.

After five years of official Conference, paralyzed in its progress during the COVID-19 pandemic, a rational text is currently being considered, awaiting finalization. At the fifth session, held in August 2022, some sticking points could not be resolved, such as the status of digital genetic data, the process to create MPAs or the issues of research funding for developing countries. But we are almost there. The year 2023 marks the 50th anniversary of the writing of the Montego Bay Convention: it is time to go all the way through, to let go of national interests in the name of this half of the globe that we have the opportunity to set up as an example of a common good, managed collectively for the sake of the planet and of living beings.

Understanding and protecting the high sea: the commitment of the Tara Ocean Foundation

For 20 years, the Tara Ocean Foundation sails through the high sea for its scientific expeditions. Thanks to the knowledge developed on board its schooner alongside its partner laboratories, the Foundation endeavors the consideration of high sea biodiversity since the beginning of the treaty.

In 2010, the schooner Tara was in the middle of its Tara Oceans expedition, a planetary adventure at the basis of an innovative and multidisciplinary science on plankton. In October of that year, the Tara team made a stopover in Rio de Janeiro in Brazil, which was at the time a champion of multilateralism and driven by the ambition to successfully handle its environmental conference two years later. It was during this Brazilian stopover that the Mayor of Rio asked the Tara Ocean Foundation to take on the role of Ambassador for the Rio+20 Conference on the Ocean’s issues. Tara thus embarked on this adventure, which was embodied during a stopover in New York in January 2012, which represented the beginning of our activity at the United Nations. During this stopover, the UN Secretary General, Ban Ki-Moon, came on board during an afternoon to meet the sailors and researchers. He reaffirmed at this moment the importance of negotiations for the high sea and invited Tara to get involved in the negotiations. The Tara Foundation has thus organized a Blue Pavilion at Rio+20, to host events, presentations, projections and discussions on the Ocean, particularly on the high sea.

In 2013, the UN granted the Foundation the status of Special Observer, thus allowing the Tara Ocean Foundation to participate actively in the negotiations, officially initiated that same year at the UN headquarters in New York. From the very first negotiation sessions, we realized the considerable work needed to make the negotiators and ambassadors understand the importance and the key role of plankton in the high sea.

With the participation of partner researchers, the Foundation was present at almost every negotiation session at the UN, in close collaboration with the delegations of the European Union, France, Brazil, Monaco and Chile. In this interface between science and UN experts, we developed an advocacy for an universal, ambitious and united agreement, integrating the need to support international research. Research on the open ocean requires science that is effectively international, robust, cooperative and open to society. It must be disinterested and generous in data sharing, involving developing countries and training young researchers.

Implementing the terms of the treaty: the work ahead after the next negotiating session

The Tara Ocean Foundation will be present at the next negotiation session which will take place in New York from February 20 to March 3, 2023. We hope that the States will manage to agree upon an agreement that fully integrates the ambitions we have been carrying since the beginning of the negotiations.

Once the agreement is reached, a new phase of work will begin. Our efforts will be directed towards a rapid and collective ratification of the text: quite a program for our advocacy!

The UN adopts the Treaty for the Protection of Biodiversity in the High Seas!

After fifteen years of negotiations